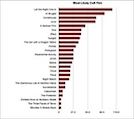

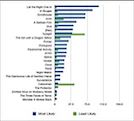

Here they are, the full results for each film.

Here they are, the full results for each film. These graphs and pie charts give a full view of how each of the 25 films that we volunteered as possible new cult films performed.

In typical cult fashion, the winner turned out not to be the winner!! In Bruges won when the poll was closed and votes were tallied on June 1st, 2011. But we left the tap open for a little while longer, and low and behold Let the Right One In pushed itself to the top position. If anything, this shows how volatile the measurement of cult reputations is: a snapshot without any claim to lasting authority.

The after-hours rush of Let the Right One In also means that the battle between zombies and vampires appears to have been won by the vampires. Even Twilight’s glittery vampires are favoured (flavoured?) above Pontypool’s zombies. To honour both types of cult creatures we include an essay on Let the Right One In and one on Pontypool further down this page.

Exploitation, gore and torture do well, as Grindhouse and Hostel testify. Yet, as if to prove that auteurism is not a done deal in cult cinema, films from established cult directors Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez and Eli Roth have to tolerate the company of titles made by talent less often hailed as ‘genius’. Without looking, who can name the directors of Let the Right One In, [Rec], or Paranormal Activity?

Science-fiction loses out to horror, in what may well be a sign of the general film climate at the beginning of the second decade of the 21st Century. But then again, Primer is, with Pontypool, Night Watch, and The Protector, the only film not to get any ‘nay’ votes. Monster X Strikes Back did not get any no-votes as well, but it hardly got any yes-votes either.

Martial arts and parody? Exploitation and camp? They have their fans, as the votes for JCVD and VIVA! demonstrate, but do they determine a film’s cult status to the extent that they suppress other points of attention? It seems not. Rather, it looks like cult films can only have multiple, aggregate identities – instead of being ‘this’ or ‘that’ they are ‘mish and mash’.

To illustrate the diversity of opinions on films likely (or not) to be cult, we have assembled a variety of views that reflect on the films in our poll, from tortured love letters over raised eyebrows to some heavy theorizing.

Juno

By Emily Perkins

Is Juno the safest possible choice for a cult film? If so, Juno’s inclusion in the top four of our survey of ‘newest cults,’ and its high score as a film ‘least likely’ to be cult, says something about how the concept of cult is defaulting into the mainstream. Because you couldn’t design a film to appeal to the mainstream more than Juno does. It is not so much the blockbuster-mainstream with which it finds a warm welcome, but the inoffensive mainstream that defuses issues instead of letting them explode.

One of the major culture wars in North America is the one over teen pregnancies. With its incredibly light touch, Juno manages to dance across the surface of this murky bog without getting mired in the muck. It transcends, or perhaps avoids, the politics of its subject matter (teen pregnancy and child adoption) through highly stylized whip-smart dialogue and an ambience of kitschy nostalgia. It looks as if what matters isn’t the seriousness of the situation Juno finds herself in, what matters is its aesthetic. The T-shirts, bags and the hamburger-phone seem to belong to a virtually computer-less and cell phone-less world of the past. Yet the film is not set in a specific period – as if Juno and other characters (especially adoptive father-to-be Mark Loring), are locked up in childhood forever, cozy and safe. What Juno offers is a brush with adulthood and an escape from that experience, so that with Juno viewers can say they survived, almost grew up, but in the end didn’t have to.

Juno’s look brings with itself a lack of moral graveness. Perhaps the reason we don’t judge Ellen Page’s Juno harshly is because her body is so contained: she has the physical features of an eleven-year-old boy with a basketball in front. There is nothing threatening about her. Her clothes are decidedly non-sexual, and so is her behaviour; her engagement with sex is more like a one-time experiment instead of anything as messy as real desire or hormonal lust. In the eyes of adults Juno is sweetly vulnerable, and in the eyes of a teen audience her slightly cynical attitude is ‘cool.’ The result is that she avoids judgment from any generation or camp.

Sometimes Juno does get close to addressing transgression, for instance when Juno and Mark get to know each other a bit better through an in-depth discussion over the finer points of gore in the oeuvres of Dario Argento and Hershell Gordon Lewis (favoured by Juno and Mark respectively). It is a nice intertextual nod to cult heritage (one of many in the film), and a proxy effort to introduce the subject of abject bodies or taboo fluids (via the self-reflexive intermediate of a television screen). But again, Juno only skirts the issue and then gracefully declines to commit to a real position on the matter. Unless it would be that the viewer is asked to consider Argento to be the more reliable reference because the plot reveals H.G. Lewis fan Mark to back out of his responsibilities as a dad-in-waiting (and even that failure is not judged too harshly). Perhaps that is why Juno can be a cult film: because it stubbornly remains a true triumph of inconsequence and everlasting purity, and because it replaces dogma and doxa with trivia.

Grindhouse

Dana Keller and Rovin Onas

Grindhouse, the 2007 double feature comprising Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror and Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof, is a love letter to the “grindhouse” theatres of the 60s and 70s that specialized in screening exploitation flicks and B-movies. It’s not a sweet lover letter though — not one of those which is accompanied by chocolates and roses — it’s more like a creepy ransom note wrapped around a human ear. Like the most passionate, obsessive lover, Grindhouse is excessive in its attempts to prove itself: it can’t just be an homage to the grindhouse films of yore, it needs to actually be those films. In its quest for authenticity, Grindhouse even provides its audience with trailers for fake films directed by Eli Roth, Rob Zombie and Edgar Wright — two of these (Machete and Hobo With a Shotgun) have since been adapted into full-length features.

Planet Terror asks the question, what happens when biological weapons land in the wrong hands? The answer is mutants, zombies, murderous mayhem and... sexy nurses? Oh yeah, and a pinup-girl go-go dancer named Cherry Darling with a machine gun for a leg. Death Proof is arguably more grounded in reality, or perhaps more accurately, its monsters aren’t of the undead variety. The villain (or villain-hero, depending on which way you look at it) of Death Proof is Stuntman Mike, who is, well, a stuntman, with a “death proof” car — on the driver’s side, at least. Stuntman Mike gets his kicks picking up hot young girls and demolishing his car with them in the passenger seat. He likes to watch them squirm before they die — and of course, he likes to watch them die, too.

Voluptuous babes, unlikely heroes (sometimes these are one and the same) and sets so hot the screen sweats give Grindhouse a gritty, organic presence that stains the mind and is hard to wash off. Add to this cameo appearances by A-list actor Josh Brolin, retro icon Kurt Russell and real-life stunt double Zoe Bell (Xena, Kill Bill), and it’s hard to deny that Grindhouse has, at the very least, cult potential. Whether it succeeds at being a cult film or not is still up for debate.

Many of our respondents — even the ones who voted in favour of Grindhouse as the next new cult film — remarked that it tried too hard to be cult. Oddly, and much like that impassioned lover who sometimes meets with success, Grindhouse’s excessive attempts at being authentic could arguably be what has garnered it its following. As one of our respondents wrote: “Grindhouse is a B-movie that tried so hard to be a B-movie and succeeded.”

In its reception at least, the film seems to be following the traditional cult film trajectory. Although a box office flop despite mostly positive reviews, Grindhouse seemed to gain a greater following upon its DVD release in which the films were presented separately in extended cuts. Cult films often underperform at the box office, only to gain a rabid fanbase through less official (read private, illegal, or at the very least, unconventional) screenings, so Grindhouse can at the very least check that off its list. As for the rest, only time will tell!

Let The Right One In

By Ernest Mathijs

At face value, Swedish vampire movie Let The Right One In follows the trend, popularized by Twilight, of presenting prudish predators, the vampire as your abstaining friend for whom any explicit languishing for sex is thoroughly suppressed. In this case, the protagonists, blond and angelic Oskar, and his new neighbor the enigmatic child-vampire Eli, are only 12 years old, almost pre-sexual (although, of course, she is really hundreds of years old). Oskar is bullied by his classmates and though he dreams of getting even, he remains passive – ‘squeal piggy’ he whispers as he pretend-avenges himself on a tree outside his apartment building. Eli teaches him to stand up for himself. “Be me a little,” she tells him. He tries, but his actions come back with a vengeance. In a spine-chilling bloodbath climax, Eli’s superpowers save Oskar. The end sees the angel and his devilish guardian travel off together.

Throughout the film white, pale pallets abound. Punctured spots of red intervene in this snowy, sleepy, dreamy (and strictly rectangular) design. Set in the early 1980s, there are no social media, no frantic chatter to relieve the sense of isolation. Into this constellation comes the dark, brooding Eli, a guest who may or may not be welcome. The title of the film refers to the fact that, according to part of the vampire myth, vampires have to be invited into the door by their victims. Oskar first refuses. Only after Eli almost bleeds to death because of his reluctance does he give in. Let The Right One In asks the uncomfortable question if hospitality means one has to accept the bad with the good. A pointed comment on immigration?

Like most horror movies today, Let The Right One In acknowledges its predecessors. As if to hammer that home, a chainsaw is produced to cut through thick ice to defrost a victim. It provides one moment for fan-chuckling in an otherwise deadly depressive atmosphere.

Speaking of fans, Let the Right One In was one of the top-scoring films in our survey. If one ignores the cut-off date of the survey it even had the highest number of votes. Other than that this demonstrates the enduring and entrenched popularity of the film with horror cultists, it also says something about how deep the care for this film goes – beyond time almost (many fans disagreed even that it was a “new” cult film, and suggested it has been around “forever”). One commentator compared the film’s lasting impact to Eli herself: “it will outlast all others.”

Once

By Brent Strang

If my sickness for the saccharine and sincere has me clicking through hours of Youtube clips of James Taylor and John Prine, I might just idle a bit longer and watch Once. Cult films aren’t usually so gentle, but still, this one rouses in me the same level of cathexis. My unhealthy addiction for sap often brings me to the couch for such occasions to see if the meniscus of tear under my eyes will break and seep a little.

Here, a beaten lover from Dublin takes an optimistic turn for a second go at love’s sweet prison. There’s a girl who’s terribly fond of him but is heedful, since she can tell he’s stuck on his ex. As long as the story sticks to this and has them singing about such things, it works. Thankfully, it spares us seeing him and his girlfriend actually reuniting—or worse, two or three months or years down the road, when things likely turn again into the same old crap. Instead, we may still get carried away in believing love’s bonds are as captivating as the throats of these musicians. It’s when artists are alone and broken-hearted that they’re supposed to write the best music, right? That’s when they sing best, too, this movie reminds us, and as if to press that point just a little bit harder, Once lovingly winks an eye at tough-but-sweet hardrock band Thin Lizzy, and its achingly romantic singer Phil Lynott.

Argue Once is a cult film and you’re liable to lose on every point; I’d wager most cult audiences would rather throw up in their mouths than swallow an ounce of Once’s cleansing (Pla)tonic mouthwash-for-fools. As for me, I’d rather just avow I’m in the ‘cult of Once’ and let them argue there’s no such thing. They can quietly judge me if they want… mock me with a postmodern insouciance. That’s okay. I’ve been spotted weeping profusely during Meet Joe Black and Dead Poet’s Society, and I’ve learned to bear it.

Pontypool

By Dana Keller

We all mix up our words sometimes. Often we don’t even realize we’ve done it until someone points it out. This usually results in (hopefully) mutual laughter — it’s no big deal — and life goes on. But in Bruce McDonald’s Pontypool, mixing up one’s words is a symptom of a deadly disease that almost inevitably ends in a horrible, violent, gory demise. But if English isn’t your first language, you have nothing to worry about — at least, not yet. This plot point feels particularly political given the film’s setting in a small Canadian town (called Pontypool), recalling a history of tensions between Canada’s francophone and anglophone citizens — tensions that are heightened perhaps within the film when French riot police arrive on the scene in an attempt to control the situation.

Despite the horrific things that happen in the film, Pontypool can be viewed as a twisted love song to the snowy, isolated, quirky Canada so often depicted in TV shows and films (Strange Brew, Fubar, Northern Exposure and Corner Gas to name a few). Perhaps it is the film’s Canadianess that sets it apart from a lot of other horror films. And this doesn’t stop at Pontypool’s content: Canadian filmmakers seem almost stubbornly resistant to adopting the style and rhythm of Hollywood films, and Pontypool takes this to an extreme.

While the stereotypical horror film boasts excessive style, much of Pontypool looks like a filmed radio play. Trapped inside the radio station and frustrated by his inability to ascertain what is going on outside, Grant Mazzy, the film’s shock jock protagonist, says, “French philosopher Roland Barthes once described trauma as a news photo without a caption, and that folks is what I think we have here now.” Ironically, the film itself is the exact opposite of Mazzy’s quote: all caption and barely any photo. This is perhaps what makes the film so frightening despite its sparse visuals: in a film where the virus spreads through language, what one hears is infinitely more dangerous than what one sees. In this sense watching Pontypool becomes similar to watching The Ring in that it is a film that self-reflexively pushes the danger within its plot back out onto its audience.

Pontypool may have received only a small number of votes (under 20) in the section of our survey which asked participants to name up to three future cult films, but it was never once voted as least likely to become a cult film. Participants who voted for Pontypool listed both formal and contextual elements as the factors that made Pontypool a potential cult film. Among the reasons listed were its intelligence and difference from other horror (particularly zombie) films; its sound design (which has also received attention in the academic world); its low budget; and the fact that so few people seem to know about it.

[Rec]

By Russ Hunter

From Cannibal Holocaust, to The Blair Witch Project and more recently Cloverfield, the found/live-footage film has become an effective, if at times awkward, device for allowing an up-close-and-personal first-person horror experience. Spain has a particularly rich history of moody, unsettling horror films, but few are as chokingly claustrophobic as Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza’s [Rec]. One of a series of films that marked a promising revival of the Spanish horror film in the mid-2000s, it centers around the making of a TV show exploring the jobs of those who work nightshifts, the soothingly, reassuringly entitled While You Were Sleeping, presented by perky and energetic host Ángela Vidal, who is spending a shift with the local fire brigade. After a seemingly routine call out to a local apartment block in order to attend to an old woman who is trapped in her flat, things quickly turn sour, as residents of the apartment block and firefighters alike become infected by some unknown force that turns them into slavering savages. The drama unfolds ‘live’ via the crew’s cameraman Pablo and an increasingly desperate Ángela.

The live-footage conceit allows for the use of a handheld camera that – quite literally – adds an air of unsteadiness to the events. Unlike other recent examples of first-person horror, the two Spanish directors are not afraid to turn the camera off or offer a confused, blurred and – at times – chaotically disorganized frame to the viewer. This creates the increasingly frenetic and maddening atmosphere that is central to the success of the film. The dynamics of the setting – a building that very quickly becomes quarantined and therefore offers limited scope for escape – are crucial to the claustrophobic terror created by the film. The effervescent, quirky acting of former TV presenter Manuela Velasco (Ángela) also plays its part here, her gibbering and increasingly hysterical commentary adding to the sense of the building having become a kind of crazed and hyper-visceral psychiatric ward. As places to hide become fewer, very soon nothing makes any sense.

But, ultimately, [Rec] is frightening precisely because it is enigmatic, because we get close to an explanation but never fully understand what has triggered these events. Central to this is a play upon a fear of the unknown. Although we see those infected by what we learn to be an extended experiment in exorcism gone wrong, we never truly establish the extent or source of the evil present within the confines of the apartment block. And it is the film’s final image, accidentally shot with the now discarded camera’s night vision – of a broken Ángela rapidly being dragged off-screen by some unseen force – that best encapsulates the dark heart at the centre of the film.

VIVA!

By Dana Keller

Apart from one instance of an overexcited Twilight fan, VIVA!, a self-described “cult freak-out retro 1970’s spectacle, about a bored housewife who gets sucked into the sexual revolution,” is the only film in our survey whose fans saw it necessary to choose it as EACH of their top three choices – selecting it as their first, second and third favourite. This occurred several times, accompanied by hyperbolic explanations such as “Anna Biller is god!” and “It is my white horse!” Participants voted for VIVA! as the next cult film 43 times. It was only mentioned six times as the least likely to become a cult film, with one participant explaining that VIVA! does not have enough hard core fans to be cult. But the many votes and over-the-top excitement of the participants who voted for VIVA! suggest otherwise.

![Claustrophobic terror, exorcism gone wrong, and the loss of meaning: religious inferences in [Rec] (screen shot)](assets/thumbs/thumbs/rec_5_large.jpg)